Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 26:1 | Like as snowe is not mete in sommer, ner rayne in haruest: euen so is worshipe vnsemely for a foole. |

| 26:2 | Like as ye byrde and the swalowe take their flight and fle here and there, so the curse that is geuen in vayne, shal not light vpon a man. |

| 26:3 | Vnto the horse belongeth a whyppe, to the Asse a brydle, and a rodde to the fooles backe. |

| 26:4 | Geue not the foole an answere after his foolishnesse, lest thou become like vnto him: |

| 26:5 | but make ye foole an answere to his foolishnesse, lest he be wyse in his owne coceate. |

| 26:6 | He is lame of his fete, yee droncken is he in vanite, that comitteth eny thinge to a foole. |

| 26:7 | Like as it is an vnsemely thige to haue legges & yet to halte, eue so is a parable in ye fooles mouth. |

| 26:8 | He yt setteth a foole in hye dignite, yt is eue as yf a man dyd cast a precious stone vpo ye galous. |

| 26:9 | A parable in a fooles mouth, is like a thorne yt pricketh a droncken man in ye hande. |

| 26:10 | A man of experience discerneth all thinges well, but whoso hyreth a foole, hyreth soch one as wyl take no hede. |

| 26:11 | Like as the dogg turneth agayne to his vomite, euen so a foole begynneth his foolishnesse agayne afresh. |

| 26:12 | Yf thou seyest a man yt is wyse in his owne conceate, there is more hope in a foole then in hi. |

| 26:13 | The slouthfull sayeth: there is a leoparde in ye waye, and a lyon in ye myddest of the stretes. |

| 26:14 | Like as the dore turneth aboute vpon the tresholde, euen so doth the slouthfull welter himself in his bedd. |

| 26:15 | The slouthfull body thrusteth his hode in to his bosome, and it greueth him to put it agayne to his mouth. |

| 26:16 | The slogarde thinketh him self wyser, then vij. men that sytt and teach. |

| 26:17 | Who so goeth by and medleth with other mens strife, he is like one yt taketh a dogg by ye eares. |

| 26:18 | Like as one shuteth deadly arowes and dartes out of a preuy place, euen so doth a dyssembler with his neghboure, |

| 26:19 | And then sayeth he: I dyd it but in sporte. |

| 26:20 | Where no wodd is, there the fyre goeth out: and where the bacbyter is taken awaye, there the strife ceaseth. |

| 26:21 | Coles kyndle heate, and wodd ye fyre: euen so doth a braulinge felowe stere vp variaunce. |

| 26:22 | A slaunderers wordes are like flatery, but they pearse ye inwarde partes of ye body. |

| 26:23 | Venymous lippes & a wicked herte, are like a potsherde couered wt syluer drosse. |

| 26:24 | An enemie dyssembleth with his lippes, and in the meane season he ymagineth myschefe: |

| 26:25 | but wha he speaketh fayre, beleue him not, for there are seuen abhominacios in his herte. |

| 26:26 | Who so kepeth euell will secretly to do hurte, his malyce shalbe shewed before the whole congregacion. |

| 26:27 | Who so dyggeth vp a pytt, shal fal therin: and he yt weltreth a stone, shal stomble vpon it hymselfe. |

| 26:28 | A dyssemblynge tonge hateth one that rebuketh him, and a flaterige mouth worketh myschefe. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

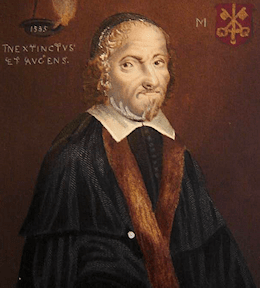

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.