Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 13:1 | A wyse sonne wyll receaue his fathers warnynge, but he yt is scornefull, wyll not heare when he is reproued. |

| 13:2 | A good ma shal enioye the frute of his mouth, but he that hath a frowarde mynde, shalbe spoyled. |

| 13:3 | He that kepeth his mouth, kepeth his life: but who so speaketh vnaduysed, fyndeth harme. |

| 13:4 | The slogarde wolde fayne haue, and can not get his desyre: but the soule of the diligent shal haue plenty. |

| 13:5 | A righteous man abhorreth lyes, but the vngodly shameth both other and himself. |

| 13:6 | Righteousnesse kepeth the innocet in the waye, but vngodlynesse shal ouerthrowe the synner. |

| 13:7 | Some men are riche, though they haue nothinge: agayne, some me are poore hauynge greate riches. |

| 13:8 | With goodes euery man delyuereth his life, and the poore wyl not be reproued. |

| 13:9 | The light of the righteous maketh ioyfull, but the candle of the vngodly shal be put out. |

| 13:10 | Amonge the proude there is euer strife, but amonge those that do all thinges with aduysement, there is wy?dome. |

| 13:11 | Hastely gotte goodes are soone spent, but they that be gathered together with the hande, shal increase. |

| 13:12 | Longe tarienge for a thinge that is dyfferred, greueth ye herte: but when the desyre commeth, it is a tre of life. |

| 13:13 | Who so despyseth the worde, destroyeth himself: but he that feareth the comaundement, shal haue peace. |

| 13:14 | The lawe is a wel of life vnto the wyse, that it maye kepe him from the snares of death. |

| 13:15 | Good vnderstondinge geueth fauoure, but harde is the waye of the despysers. |

| 13:16 | A wyse man doth all thinges with discrecion, but a foole wil declare his foly. |

| 13:17 | An vngodly messauger bryngeth myschefe, but a faithfull embassitoure is wholsome. |

| 13:18 | He that thinketh scorne to be refourmed, commeth to pouerte and shame: but who so receaueth correccion, shal come to honoure. |

| 13:19 | When a desyre is brought to passe, it delyteth the soule: but fooles abhorre him that eschueth euell. |

| 13:20 | He that goeth in the company of wyse men, shal be wyse: but who so is a copanyo of fooles, shal be hurte. |

| 13:21 | Myschefe foloweth vpon synners, but the rightuous shal haue a good rewarde. |

| 13:22 | Which their childers childre shal haue in possessio, for the riches of the synner is layed vp for ye iust. |

| 13:23 | There is plenteousnesse of fode in the feldes of the poore, & shalbe increased out of measure. |

| 13:24 | He that spareth the rodde, hateth his sonne: but who so loueth him, holdeth him euer in nurtoure. |

| 13:25 | The rightuous eateth, and is satisfied, but ye bely of the vngodly hath neuer ynough. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

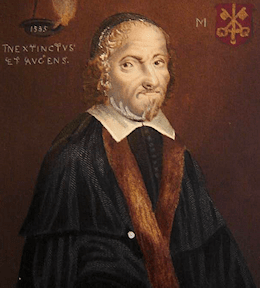

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.