Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 22:1 | A good name is more worth then greate riches, and louynge fauor is better then syluer and golde. |

| 22:2 | Whether riches or pouerte do mete vs, it commeth all of God. |

| 22:3 | A wyse man seyth the plage and hydeth himself, but the foolish go on still and are punyshed. |

| 22:4 | The ende of lowlynes & the feare of God, is riches, honor, prosperite and health. |

| 22:5 | Speares and snares are in ye waye of the frowarde, but he yt wil kepe his soule, let him fle fro soch. |

| 22:6 | Yf thou teachest a childe in his youth what waye he shulde go, he shall not leaue it when he is olde. |

| 22:7 | The rich ruleth the poore, and ye borower is seruaunt to ye lender. |

| 22:8 | He yt soweth wickednesse, shal reape sorowe, & the rodde of his plage shal destroye him. |

| 22:9 | A louynge eye shalbe blessed, for he geueth of his bred vnto ye poore. |

| 22:10 | Cast out ye scornefull man, and so shal strife go out wt him, yee variaunce and slaunder shal cease. |

| 22:11 | Who so delyteth to be of a clene herte and of gracious lyppes, ye kynge shal be his frende. |

| 22:12 | The eyes of ye LORDE preserue knowlege, but as for ye wordes of ye despyteful, he bryngeth them to naught. |

| 22:13 | The slouthfull body sayeth: there is a lyo wt out, I might be slayne in ye strete. |

| 22:14 | The mouth of an harlot is a depe pytt, wherin he falleth that ye LORDE is angrie withall. |

| 22:15 | Foolishnes sticketh in the herte of ye lad, but ye rod of correccion driueth it awaye. |

| 22:16 | Who so doth a poore man wronge to increase his owne riches, geueth (comoly) vnto the rich, and at the last commeth to pouerte himself. |

| 22:17 | My sonne, bowe downe thine eare, and herken vnto the wordes of wy?dome, applye yi mynde vnto my doctryne: |

| 22:18 | for it is a pleasaunt thinge yf thou kepe it in thine herte, and practise it in thy mouth: |

| 22:19 | that thou mayest allwaye put yi trust in the LORDE. |

| 22:20 | Haue not I warned ye very oft with councell and lerninge? |

| 22:21 | yt I might shewe ye the treuth and that thou wt the verite mightest answere them yt laye eny thinge against ye? |

| 22:22 | Se yt thou robbe not ye poore because he is weake, and oppresse not ye simple in iudgment: |

| 22:23 | for ye LORDE himself wyl defende their cause, and do violence vnto them yt haue vsed violence. |

| 22:24 | Make no fredshipe with an angrie wylfull man, and kepe no company wt ye furious: |

| 22:25 | lest thou lerne his wayes, and receaue hurte vnto thy soule. |

| 22:26 | Be not thou one of them yt bynde ther hande vpo promyse, and are suertie for dett: |

| 22:27 | for yf thou hast nothinge to paye, they shal take awaye thy bed from vnder the. |

| 22:28 | Thou shalt not remoue the lande marcke, which thy fore elders haue sett. |

| 22:29 | Seist thou not, yt they which be diligent in their busines stonde before kynges, and not amonge the symple people? |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

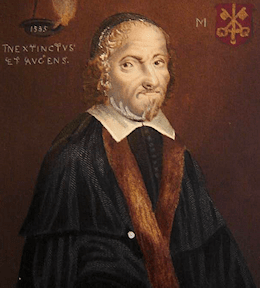

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.