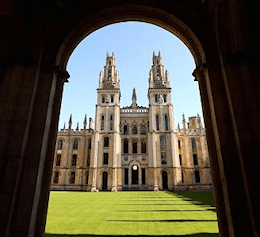

Textus Receptus Bibles

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 92:1 | It is a good thing to give thanks unto the LORD, and to sing praises unto thy name, O most High: |

| 92:2 | To shew forth thy lovingkindness in the morning, and thy faithfulness every night, |

| 92:3 | Upon an instrument of ten strings, and upon the psaltery; upon the harp with a solemn sound. |

| 92:4 | For thou, LORD, hast made me glad through thy work: I will triumph in the works of thy hands. |

| 92:5 | O LORD, how great are thy works! and thy thoughts are very deep. |

| 92:6 | A brutish man knoweth not; neither doth a fool understand this. |

| 92:7 | When the wicked spring as the grass, and when all the workers of iniquity do flourish; it is that they shall be destroyed for ever: |

| 92:8 | But thou, LORD, art most high for evermore. |

| 92:9 | For, lo, thine enemies, O LORD, for, lo, thine enemies shall perish; all the workers of iniquity shall be scattered. |

| 92:10 | But my horn shalt thou exalt like the horn of an unicorn: I shall be anointed with fresh oil. |

| 92:11 | Mine eye also shall see my desire on mine enemies, and mine ears shall hear my desire of the wicked that rise up against me. |

| 92:12 | The righteous shall flourish like the palm tree: he shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon. |

| 92:13 | Those that be planted in the house of the LORD shall flourish in the courts of our God. |

| 92:14 | They shall still bring forth fruit in old age; they shall be fat and flourishing; |

| 92:15 | To shew that the LORD is upright: he is my rock, and there is no unrighteousness in him. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.