Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 8:1 | BenIamin begat Bela his fyrst sonne, A?bal the secode, Ahrah ye thirde, |

| 8:2 | Noah the fourth, Rapha the fyfth. |

| 8:3 | And Bela had children: Gera, Abihud, |

| 8:4 | Abisua, Neman, Ahoah, |

| 8:5 | Gera, Sphuphan and Huram. |

| 8:6 | These are Ehuds children, which were heades of the fathers amonge the citesyns at Geba, and wete awaye vnto Manahath, |

| 8:7 | namely Naeman, Ahia and Gera, the same caryed them awaye, and begat Vsa and Ahihud. |

| 8:8 | And Seharaim (whan he had sent the awaye) begat children in the londe of Moab of Husim and Baera his wyues. |

| 8:9 | And of Hodes his wyfe begat he Iobab, Zibea, Mesa, Malcham, |

| 8:10 | Ieus, Sachia, and Mirma, these are his children, heades of the fathers. |

| 8:11 | Of Husim begat he Ahitob and Elpaal. |

| 8:12 | The childre of Elpaal were: Eber, Miseam and Samed. The same buylded Ono & Lod and the vyllages therof. |

| 8:13 | And Bria and Sama were heades of the fathers amonge the citesyns at Aialon. These chaced awaye the of Gath. |

| 8:14 | His brethre Sasak, Ieremoth, |

| 8:15 | Sebadia, Arad, Ader, |

| 8:16 | Michael, Iespa and Ioha, these are the children of Bria. |

| 8:17 | Sebadia Mesullam, Ezechi, Heber, |

| 8:18 | Iesmerai, Ieslia, Ioab, these are ye childre of Elpaal. |

| 8:19 | Iakim Sichri, Sabdi, |

| 8:20 | Eloenai, Zilthai, Eliel, |

| 8:21 | Adaia, Braia and Simrath, these are the childre of Semei. |

| 8:22 | Iespan, Eber, Eliel, |

| 8:23 | Abdon, Sichri, Hanan, |

| 8:24 | Hanania, Elan, Enthothia, |

| 8:25 | Iephdeia and Penuel, these are the children of Sasak. |

| 8:26 | Samserai, Seharia, Athalia, |

| 8:27 | Iaeresia, Elia and Sichri, these are, the children of Ieroham. |

| 8:28 | These are the heades of the fathers of their kynreds, which dwelt at Ierusalem. |

| 8:29 | But at Gibeon dwelt, the father of Gibeon, & his wyues name was Maecha, |

| 8:30 | and his first sonne was Abdon, Zur, Cis, Baal, Nadab, |

| 8:31 | Gedor, Ahio and Secher. |

| 8:32 | Mikloth begat Simea. And they dwelt ouer agaynst their brethre at Ierusalem with theirs. |

| 8:33 | Ner begat Cis. Cis begat Saul. Saul begat Ionathas, Melchisua, Abinadab and Esbaal. |

| 8:34 | The sonne of Ionathas was Meribaal. Meribaal begat Micha. |

| 8:35 | The children of Micha were: Pithon, Melech, Thaerea and Ahas. |

| 8:36 | Ahas begat Ioadda. Ioadda begat Alemeth, Asmaueth and Simri. Simri begat Moza. |

| 8:37 | Moza begat Binea, whose sonne was Rapha, whose sonne was Eleasa, whose sonne was Azel. |

| 8:38 | Azel had sixe sonnes, whose names were: Esricam, Bochru, Iesmael, Searia, Abadia, Hanan, all these were the sonnes of Azel. |

| 8:39 | The children of Esek his brother were: Vlam his first sonne, Ieus the seconde, Elipelet the thirde. |

| 8:40 | The children of Vlam were valeaunt men, and coulde handell bowes, and had many sonnes, and sonnes sonnes an hundreth and fiftye. All these are of the children of Ben Iamin. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

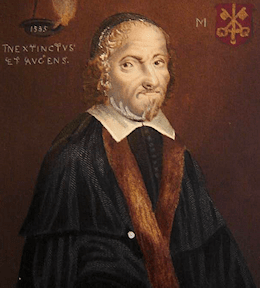

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.