Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 29:1 | So Iob proceaded and wete forth in his communicacion, sayenge: |

| 29:2 | O yt I were as I was in the monethes by past, & in the dayes whe God preserued me: |

| 29:3 | when his light shyned vpon my heade: whe I wente after the same light & shyne eue thorow the darcknesse. |

| 29:4 | As it stode wt me, whe I was welthy & had ynough: whe God prospered my house: |

| 29:5 | when the allmightie was with me: when my housholde folkes stode aboute me: |

| 29:6 | whe my wayes ranne ouer wt butter, & when the stony rockes gaue me ryuers of oyle: |

| 29:7 | when I wente thorow the cite vnto the gate, & whe they set me a chayre in ye strete: |

| 29:8 | whe the yonge me (as soone as they sawe me) hyd the selues, & when the aged arose, & stode vp vnto me: |

| 29:9 | whe the princes left of their talkinge, & laied their hade to their mouth: |

| 29:10 | whe the mightie kepte still their voyce, and whe their tonges cleued to the rofe of their mouthes. |

| 29:11 | When all they yt herde me, called me happie: & when all they yt sawe me, wysshed me good. |

| 29:12 | For I delyuered ye poore whe he cried, & the fatherlesse yt wanted helpe. |

| 29:13 | He yt shulde haue bene lost, gaue me a good worde, & ye widdowes hert praised me. |

| 29:14 | And why? I put vpon me rightuousnes, which couered me as a garmet, & equite was my crowne. |

| 29:15 | I was an eye vnto the blynde, & a fote to the lame. |

| 29:16 | I was a father vnto the poore, & whe I knew not their cause, I sought it out diligetly. |

| 29:17 | I brake the chaftes of ye vnrightuous, & plucte the spoyle out of their teth. |

| 29:18 | Therfore, I thought verely, yt I shulde haue dyed in my nest: & yt my dayes shulde haue bene as many as the sondes of the see. |

| 29:19 | For my rote was spred out by the waters syde, & the dew laye vpo my corne. |

| 29:20 | My honor encreased more & more, and my bowe was euer the stronger in my hande. |

| 29:21 | Vnto me men gaue eare, me they regarded, & wt sylence they taried for my coucell. |

| 29:22 | Yf I had spoken, they wolde haue it none other wayes, my wordes were so well taken amonge the. |

| 29:23 | They wayted for me, as the earth doth for the rayne: & gaped vpon me, as the groude doth to receaue the latter shower. |

| 29:24 | When I laughed, they knew well it was not earnest: & this testimony of my coutenaunce pleased the nothinge at all. |

| 29:25 | When I agreed vnto their waye, I was the chefe, & sat as a kynge amonge his seruauntes: Or as one that comforteth soch as be in heuynesse. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

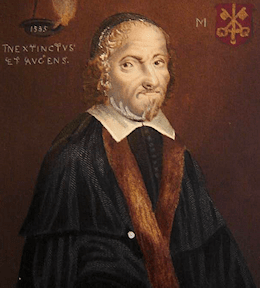

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.