Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 13:1 | Lo, all this haue I sene with myne eye, herde with myne eare, & vnderstonde it. |

| 13:2 | Loke what ye knowe, that same do I knowe also, nether am I inferior vnto you. |

| 13:3 | Neuerthelesse I am purposed to talke with the Allmightie, and my desyre is to comon with God. |

| 13:4 | As for you, ye are workmasters of lyes: and vnprofitable Phisicians alltogether. |

| 13:5 | Wolde God ye kepte youre tonge, that ye might be taken for wyse men. |

| 13:6 | Therfore heare my wordes, and pondre the sentence of my lippes. |

| 13:7 | Will ye make answere for God with lyes, and mateyne him with disceate? |

| 13:8 | Wil ye accepte ye personne of God, and intreate for him? |

| 13:9 | Shal that helpe you, when he calleth you to rekenynge? Thynke ye to begyle him, as a man is begyled? |

| 13:10 | Punysh you shall he and reproue you, yf ye do secretly accepte eny personne. |

| 13:11 | Shall he not make you afrayed, when he sheweth himself? Shal not his terrible feare fall vpo you? |

| 13:12 | youre remembraunce shalbe like the dust, & youre pryde shalbe turned to claye. |

| 13:13 | Holde youre tonges now, and let me speake, for there is some thinge come in to my mynde. |

| 13:14 | Wherfore do I beare my flesh in my teth, and my soule in myne hondes? |

| 13:15 | Lo, there is nether coforte ner hope for me, yf he wil slaye me. But yf I shewe and reproue myne owne wayes in his sight, |

| 13:16 | he is euen the same, that maketh me whole: and why? there maye no Ypocrite come before him, |

| 13:17 | Heare my wordes, and pondre my sayenges with youre eares. |

| 13:18 | Beholde, though sentence were geuen vpon me, I am sure to be knowne for vngilty. |

| 13:19 | What is he, that will go to lawe with me? For yf I holde my tonge, I shal dye. |

| 13:20 | Neuerthelesse graunte me ij. thinges, and then will I not hyde my self from the. |

| 13:21 | Withdrawe thine honde fro me, & let not the fearfull drede of the make me afrayed. |

| 13:22 | And then sende for me to the lawe, yt I maye answere for my self: or els, let me speake, and geue thou the answere. |

| 13:23 | How greate are my my?dedes & synnes? Let me knowe my trasgressions & offences. |

| 13:24 | Wherfore hydest thou thy face, and holdest me for thine enemye? |

| 13:25 | Wilt thou be so cruell & extreme vnto a flyenge leaf, and folowe vpon drye stubble? |

| 13:26 | that thou layest so sharply to my charge, and wilt vtterly vndoo me, for ye synnes of my yougth? |

| 13:27 | Thou hast put my fote in the stockes: thou lokest narowly vnto all my pathes, & marckest the steppes of my fete: |

| 13:28 | where as I (notwithstondinge) must consume like as a foule carion, and as a cloth that is moth eaten. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

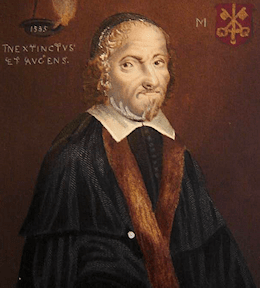

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.