Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 14:1 | Man that is borne of a woman, hath but a shorte tyme to lyue, and is full of dyuerse miseries. |

| 14:2 | He cometh vp, and falleth awaye like a floure. He flyeth as it were a shadowe, and neuer continueth in one state. |

| 14:3 | Thinkest thou it now well done, to open thine eyes vpon soch one, and to brynge me before the in iudgment? |

| 14:4 | Who can make it cleane, that commeth of an vncleane thinge? No body. |

| 14:5 | The dayes of man are shorte, ye nombre of his monethes are knowne only vnto the. Thou hast apoynted him his boundes, he can not go beyonde them. |

| 14:6 | Go from him, that he maye rest a litle: vntill his daye come, which he loketh for, like as an hyrelinge doth. |

| 14:7 | Yf a tre be cutt downe, there is some hope yet, that it will sproute and shute forth the braunches againe: |

| 14:8 | For though a rote be waxen olde and deed in the grounde, yet whe the stocke |

| 14:9 | getteth the sent of water, it will budde, and brynge forth bowes, like as when it was first planted. |

| 14:10 | But as for man, when he is deed, perished and consumed awaye, what becommeth of him? |

| 14:11 | The floudes when they be dryed vp, & the ryuers when they be emptie, are fylled agayne thorow the flowinge waters of the see: |

| 14:12 | but when man slepeth, he ryseth not agayne, vntill the heauen perish: he shal not wake vp ner ryse out of his slepe. |

| 14:13 | O that thou woldest kepe me, and hyde me in the hell, vntill thy wrath were stilled: & to appoynte me a tyme, wherin thou mightest remembre me. |

| 14:14 | Maye a deed man lyue agayne? All the dayes of this my pilgremage am I lokynge, when my chaunginge shal come. |

| 14:15 | Yf thou woldest but call me, I shulde obeie the: only despyse not the worke of thine owne hondes. |

| 14:16 | For thou hast nombred all my goynges, yet be not thou to extreme vpon my synnes. |

| 14:17 | Thou hast sealed vp myne offences, as it were in a bagg: but be mercifull vnto my wickednesse. |

| 14:18 | The mountaynes fall awaye at the last, the rockes are remoued out of their place, |

| 14:19 | the waters pearse thorow the very stones by litle and litle, the floudes wa?she awaye the grauell & earth: Euen so destroyest thou the hope of man in like maner. |

| 14:20 | Thou preuaylest agaynst him, so that he passeth awaye: thou chaungest his estate, and puttest him from the. |

| 14:21 | Whether his children come to worshipe or no, he can not tell: And yf they be men of lowe degre, he knoweth not. |

| 14:22 | Whyle he lyueth, his flesh must haue trauayle: and whyle the soule is in him, he must be in sorowe. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

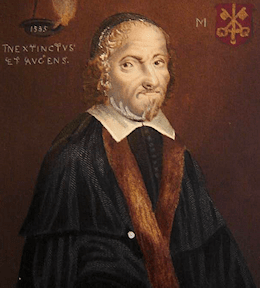

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.