Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 28:1 | There are places where syluer is molte, & where golde is tryed: |

| 28:2 | where yron is dygged out of the grounde, & stones resolued to metall. |

| 28:3 | The darcknes shal once come to an ende, he can seke out the grounde of all thinges: the stones, the darcke, & the horrible shadowe, |

| 28:4 | wt the ryuer of water parteth he a sunder the straunge people, yt knoweth no good neghbourheade: soch as are rude, vnmanerly & boysteous. |

| 28:5 | He bryngeth foode out of the earth, & yt which is vnder, consumeth he with fyre. |

| 28:6 | There is founde a place, whose stones are clene Saphirs, and where ye clottes of the earth are golde. |

| 28:7 | There is a waye also that the byrdes knowe not, that no vulturs eye hath sene: |

| 28:8 | wherin ye proude & hye mynded walke not, & where no lyon commeth. |

| 28:9 | There putteth he his honde vpon the stony rockes, & ouerthroweth the mountaynes. |

| 28:10 | Ryuers flowe out of the rockes, & loke what is pleasaunt, his eye seyth it. |

| 28:11 | Out of droppes bryngeth he greate floudes together, & the thinge that is hyd bryngeth he to light. |

| 28:12 | How commeth a man then by wy?dome? Where is the place that men fynde vnderstondinge? |

| 28:13 | Verely no man can tell how worthy a thinge she is, nether is she foude in the lode of the lyuynge. |

| 28:14 | The depe sayeth: she is not in me. The see sayeth: she is not with me. |

| 28:15 | She can not be gotten for the most fyne golde, nether maye the pryce of her be bought with eny moneye. |

| 28:16 | No wedges of golde of Ophir, no precious Onix stones, no Saphirs maye be compared vnto her. |

| 28:17 | No, nether golde ner Christall, nether swete odours ner golden plate. |

| 28:18 | There is nothinge so worthy, or so excellet, as once to be named vnto her: for parfecte wy?dome goeth farre beyonde the all. |

| 28:19 | The Topas that cometh out of Inde, maye in no wyse be lickened vnto her: yee no maner of apparell how pleasaunt and fayre so euer it be. |

| 28:20 | From whece then commeth wy?dome? & where is the place of vnderstondinge? |

| 28:21 | She is hyd from the eyes of all men, yee & fro the foules of the ayre. |

| 28:22 | Destruccion & death saie: we haue herde tell of her wt oure eares. |

| 28:23 | But God seyth hir waie, & knoweth hir place. |

| 28:24 | For he beholdeth the endes of the worlde, and loketh vpon all that is vnder the heaue. |

| 28:25 | When he weyed the wyndes, & measured ye waters: |

| 28:26 | when he set the rayne in ordre, and gaue the mightie floudes a lawe: |

| 28:27 | Then dyd he se her, the declared he her, prepared her and knewe her. |

| 28:28 | And vnto man he sayde: Beholde, to feare the LORDE, is wy?dome: & to forsake euell, is vnderstondinge. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

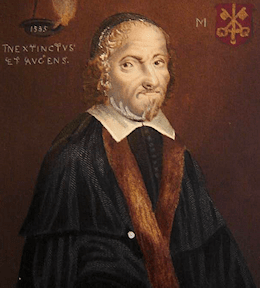

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.