Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 32:1 | Beholde, the kinge shal gouerne after ye rule of rightuousnes, and ye princes shal rule acordinge to the balaunce of equite. |

| 32:2 | He shalbe vnto me, as a defence for the wynde, and as a refuge for the tempest, like as a ryuer of water in a thurstie place, and ye schadowe of a greate rock in a drie lode. |

| 32:3 | The eyes of the seinge shall not be dymme, and the eares of them that heare, shal take diliget hede. |

| 32:4 | The hert of the vnwise, shal attayne to knowlege, and the vnparfite tuge shal speake planely and distinctly. |

| 32:5 | Then shal the nygarde be no more called gentle, ner the churle lyberall. |

| 32:6 | But the churle wil be churlishly mynded, and his hert wil worke euell and playe the ypocrite, and ymagyn abhominacios agaynst God, to make the hungrie leane, and to withholde drinke from the thurstie: |

| 32:7 | These are the perlous weapons of the cuvetous, these be his shameful councels: that he maye begyle the poore with disceatful workes, yee euen there as he shulde geue sentence with the poore. |

| 32:8 | But the liberall person ymagineth honest thinges, and commeth vp with honesty. |

| 32:9 | Vp (ye rich and ydle cities), harken vnto my voyce. Ye careles cities, marcke my wordes. |

| 32:10 | After yeares and dayes shal ye be brought in feare, o ye carelesse cities. For Haruest shalbe out, and the grape gatheringe shal not come. |

| 32:11 | O ye rich ydle cities, ye that feare no parell, ye shalbe abashed and remoued: when ye se the barennesse, the nakednesse and preparinge to warre. |

| 32:12 | Ye shal knock vpo youre brestes, because of the pleasaunt felde, and because of the fruteful vynyarde. |

| 32:13 | My peoples felde shal bringe thornes and thistels, for in euery house is voluptuousnes & in the cities, wilfulnes. |

| 32:14 | The palaces also shalbe broken, and the greatly occupide cities desolate. The towers and bulwerckes shalbe become dennes for euermore, the pleasure of Mules shalbe turned to pasture for shepe: |

| 32:15 | Vnto the tyme that ye sprete be poured vpon vs from aboue. Then shal the wildernesse be a fruteful felde & the plenteous felde shalbe rekened for a wodde. |

| 32:16 | Then shal equyte dwel in the deserte, and rightuousnesse in a fruteful londe. |

| 32:17 | And the rewarde of rightuousnesse shalbe peace, and hir frute rest and quietnesse for euer. |

| 32:18 | And my people shal dwel in the ynnes of peace, in my tabernacle and pleasure, where there is ynough in the all. |

| 32:19 | And whe the hale falleth, it shal fall in the wodde and in the citie. |

| 32:20 | O how happy shal ye be, whe ye shal safely sowe youre sede besyde all waters & dryue thither the fete of youre oxe & asses. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

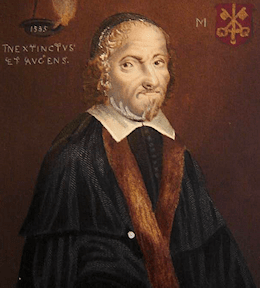

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.