Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 22:1 | And they of Ierusalem made Ochosias his yogest sonne kynge in his steade: for the men of warre that came wt the hoost of the Arabians, had slayne all ye first, therfore reigned Ochosias the sonne of Ioram kynge of Iuda. |

| 22:2 | Two and fortye yeare olde was Ochosias whan he was made kynge, and reigned one yeare at Ierusalem. His mothers name was Athalia the doughter of Amri. |

| 22:3 | And he walked also in ye wayes of the house of Achab: for his mother entysed him so yt he was vngodly. |

| 22:4 | Therfore dyd he euell in ye sighte of the LORDE, euen as ye house of Achab: for they were his councell geuers after his fathers death, to destroye him, and he walked after their councell. |

| 22:5 | And he wente with Ioram the sonne of Achab kynge of Israel, to the battayll vnto Ramoth in Gilead, agaynst Hasael the kynge of Syria. But the Syrias smote Ioram, |

| 22:6 | so yt he turned back to be healed at Iesreel: for he had woundes that were geuen him at Rama, whan he foughte with Hasael the kynge of Syria. And Asarias the sonne of Ioram kynge of Iuda wete downe to vyset Ioram ye sonne of Achab at Iesreel, which laye sicke: |

| 22:7 | For it was ordeyned of God vnto Ochosias, that he shulde come to Ioram, & so to go forth with Ioram agaynst Iehu ye sonne of Nimsi, whom the LORDE had anoynted to rote out the house of Achab. |

| 22:8 | Now whan Iehu wolde be aueged of ye house of Achab, he founde certayne rulers of Iuda, and ye childre of Ochosias brethren which serued Ochosias, and he slewe them. |

| 22:9 | And he soughte Ochosias, and they ouertoke him, wha he had hyd him at Samaria: & he was broughte vnto Iehu, which slewe him, and they buried him, for they sayde: He his the sonne of Iosaphat, which soughte ye LORDE with all his hert. And there was no man more of the house of Ochosias that mighte be kynge. |

| 22:10 | Whan Athalia the mother of Ochosias sawe yt hir sonne was deed, she gat hir vp, & destroyed all the kynges sede in the house of Iuda. |

| 22:11 | But Iosabeath ye kynges sister toke Ioas ye sonne of Ochosias, and stale him awaye fro amonge the kynges childre yt were slayne, & put him with his norse in a chamber. Thus Iosabeath kynge Iorams douhgter, the wyfe of Ioiada the prest, hyd him from Athalia, so yt he was not slayne: for she was Ochosias sister. |

| 22:12 | And he was hyd with them in the house of God sixe yeares, for so moch as Athalia was quene in the londe. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

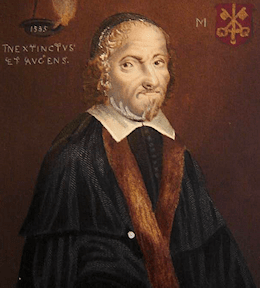

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.