Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 1:1 | This is the boke of the generacion of Iesus Christ ye sonne of Dauid, the sonne of Abraham. |

| 1:2 | Abraha begat Isaac: Isaac begat Iacob: Iacob begat Iudas & his brethre: |

| 1:3 | Iudas begat Phares & Zara of Thamar: Phares begat Hesrom: Hesrom begat Aram: |

| 1:4 | Aram begat Aminadab: Aminadab begat Naasson: Naasson begat Salmon: |

| 1:5 | Salmon begat Boos of Rahab: Boos begat Obed of Ruth: Obed begat Iesse: |

| 1:6 | Iesse begat Dauid the kynge: Dauid the kynge begat Salomon, of her that was the wyfe of Vry: |

| 1:7 | Salomon begat Roboam: Roboam begat Abia: Abia begat Asa: |

| 1:8 | Asa begat Iosaphat: Iosaphat begat Ioram: Ioram begat Osias: |

| 1:9 | Osias begat Ioatham: Ioatham begat Achas: Achas begat Ezechias: |

| 1:10 | Ezechias begat Manasses: Manasses begat Amon: Amon begat Iosias: |

| 1:11 | Iosias begat Iechonias and his brethren aboute the tyme of the captiuyte of Babylon. |

| 1:12 | And after the captiuyte of Babylon, Iechonias begat Salathiel: Salathiel begat Zorobabel: |

| 1:13 | Zorobabel begat Abiud: Abiud begat Eliachim: Eliachim begat Azor: |

| 1:14 | Azor begat Sadoc: Sadoc begat Achin: Achin begat Eliud: |

| 1:15 | Eliud begat Eleasar: Eleasar begat Matthan: Matthan begat Iacob: |

| 1:16 | Iacob begat Ioseph the hussbande of Mary, of who was borne that Iesus, which is called Christ. |

| 1:17 | All the generacions from Abraha to Dauid are fourtene generacions: From Dauid vnto the captiuite of Babylon, are fourtene generacions. From the captiuite of Babylon vnto Christ, are also fourtene generacions. |

| 1:18 | The byrth of Christ was on thys wyse: When his mother Mary was maried to Ioseph before they came together, she was foude with chylde by ye holy goost, |

| 1:19 | But Ioseph her hussbande was a perfect man, and wolde not bringe her to shame, but was mynded to put her awaie secretely. |

| 1:20 | Neuertheles whyle he thus thought, beholde, the angell of the LORDE appered vnto him in a dreame, saynge: Ioseph thou sonne of Dauid, feare not to take vnto the Mary thy wyfe. For that which is coceaued in her, is of ye holy goost. |

| 1:21 | She shall brynge forth a sonne, and thou shalt call his name Iesus. For he shall saue his people from their synnes. |

| 1:22 | All this was done, yt the thinge might, be fulfilled, which was spoken of the LORDE by the Prophet, saynge: |

| 1:23 | Beholde, a mayde shall be with chylde, and shall brynge forth a sonne, and they shall call his name Emanuel, which is by interpretacion, God wt vs. |

| 1:24 | Now whan Ioseph awoke out of slepe he did as the angell of ye LORDE bade hym, and toke his wyfe vnto hym, |

| 1:25 | and knewe her not, tyll she had brought forth hir fyrst borne sonne, and called his name Iesus. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

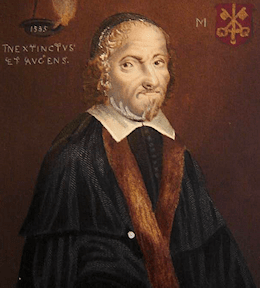

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.