Textus Receptus Bibles

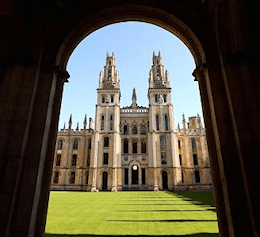

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 19:1 | The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork. |

| 19:2 | Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth knowledge. |

| 19:3 | There is no speech nor language, where their voice is not heard. |

| 19:4 | Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun, |

| 19:5 | Which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber, and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race. |

| 19:6 | His going forth is from the end of the heaven, and his circuit unto the ends of it: and there is nothing hid from the heat thereof. |

| 19:7 | The law of the LORD is perfect, converting the soul: the testimony of the LORD is sure, making wise the simple. |

| 19:8 | The statutes of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart: the commandment of the LORD is pure, enlightening the eyes. |

| 19:9 | The fear of the LORD is clean, enduring for ever: the judgments of the LORD are true and righteous altogether. |

| 19:10 | More to be desired are they than gold, yea, than much fine gold: sweeter also than honey and the honeycomb. |

| 19:11 | Moreover by them is thy servant warned: and in keeping of them there is great reward. |

| 19:12 | Who can understand his errors? cleanse thou me from secret faults. |

| 19:13 | Keep back thy servant also from presumptuous sins; let them not have dominion over me: then shall I be upright, and I shall be innocent from the great transgression. |

| 19:14 | Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O LORD, my strength, and my redeemer. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.