Textus Receptus Bibles

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 6:1 | There is an evil which I have seen under the sun, and it is common among men: |

| 6:2 | A man to whom God hath given riches, wealth, and honour, so that he wanteth nothing for his soul of all that he desireth, yet God giveth him not power to eat thereof, but a stranger eateth it: this is vanity, and it is an evil disease. |

| 6:3 | If a man beget an hundred children, and live many years, so that the days of his years be many, and his soul be not filled with good, and also that he have no burial; I say, that an untimely birth is better than he. |

| 6:4 | For he cometh in with vanity, and departeth in darkness, and his name shall be covered with darkness. |

| 6:5 | Moreover he hath not seen the sun, nor known any thing: this hath more rest than the other. |

| 6:6 | Yea, though he live a thousand years twice told, yet hath he seen no good: do not all go to one place? |

| 6:7 | All the labour of man is for his mouth, and yet the appetite is not filled. |

| 6:8 | For what hath the wise more than the fool? what hath the poor, that knoweth to walk before the living? |

| 6:9 | Better is the sight of the eyes than the wandering of the desire: this is also vanity and vexation of spirit. |

| 6:10 | That which hath been is named already, and it is known that it is man: neither may he contend with him that is mightier than he. |

| 6:11 | Seeing there be many things that increase vanity, what is man the better? |

| 6:12 | For who knoweth what is good for man in this life, all the days of his vain life which he spendeth as a shadow? for who can tell a man what shall be after him under the sun? |

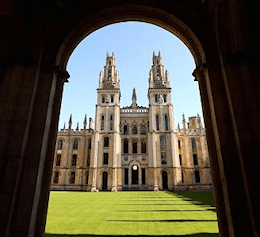

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.