Textus Receptus Bibles

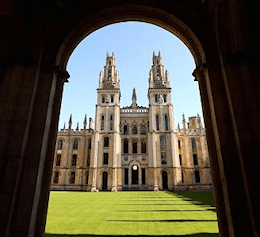

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 35:1 | Elihu spake moreover, and said, |

| 35:2 | Thinkest thou this to be right, that thou saidst, My righteousness is more than God's? |

| 35:3 | For thou saidst, What advantage will it be unto thee? and, What profit shall I have, if I be cleansed from my sin? |

| 35:4 | I will answer thee, and thy companions with thee. |

| 35:5 | Look unto the heavens, and see; and behold the clouds which are higher than thou. |

| 35:6 | If thou sinnest, what doest thou against him? or if thy transgressions be multiplied, what doest thou unto him? |

| 35:7 | If thou be righteous, what givest thou him? or what receiveth he of thine hand? |

| 35:8 | Thy wickedness may hurt a man as thou art; and thy righteousness may profit the son of man. |

| 35:9 | By reason of the multitude of oppressions they make the oppressed to cry: they cry out by reason of the arm of the mighty. |

| 35:10 | But none saith, Where is God my maker, who giveth songs in the night; |

| 35:11 | Who teacheth us more than the beasts of the earth, and maketh us wiser than the fowls of heaven? |

| 35:12 | There they cry, but none giveth answer, because of the pride of evil men. |

| 35:13 | Surely God will not hear vanity, neither will the Almighty regard it. |

| 35:14 | Although thou sayest thou shalt not see him, yet judgment is before him; therefore trust thou in him. |

| 35:15 | But now, because it is not so, he hath visited in his anger; yet he knoweth it not in great extremity: |

| 35:16 | Therefore doth Job open his mouth in vain; he multiplieth words without knowledge. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.