Textus Receptus Bibles

The History of the Textus Receptus

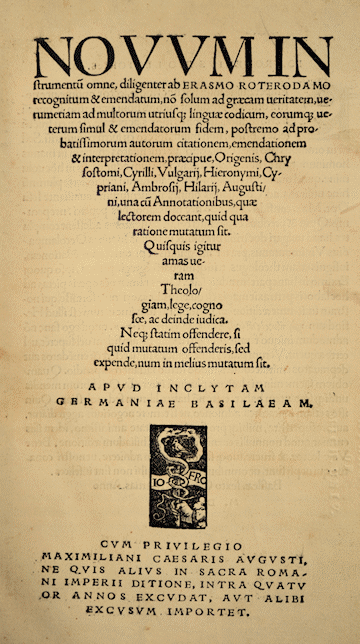

There is a great deal of misinformation regarding the origins of the Textus Receptus. This is especially true of the manner in which Desiderius Erasmus gave us his original Greek New Testament which was published in 1516. It was this work which went on to become the foundation of the Textus Receptus.

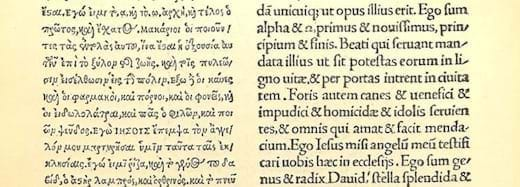

Erasmus did not invent the Textus Receptus, but simply put together a collection of what was already the vast majority of New Testament Manuscripts in the Byzantine tradition. The first Greek New Testament to be collated was the Complutensian Polyglot in (1514), but it was not published until eight years later, Erasmus' was the second Greek New Testament which was printed and published in (1516).

More than Half-Dozen Manuscripts

The fact that Erasmus had only a handful of manuscripts during his preparation of the 1516 edition is irrelevant in regards to the reliability of the text underlying his manuscript. First of all, no scholar disputes the fact that Erasmus had studied variant readings of the New Testament throughout his life prior to publishing the Textus Receptus. In fact, the study of variant readings in the Greek New Testament did not begin with Erasmus but with scholars such as Thomas Linacre (1460-1524) and John Colet (1467-1519), and even as far back as Jerome (347-420). Although Erasmus spent only two years in front of a handful of Greek manuscripts to compose his first edition, his knowledge concerning the Greek New Testament and its variants did not come solely from looking at these few manuscripts in the two year period.

Fredrick Nolan

Frederick Nolan, writing in 1815, states, in addition to the manuscripts which Erasmus owned or had seen himself, he gathered readings from various European nations through his broad friendships in universities, libraries, and monasteries. He noted; “I have a room full of letters from men of learning...” “We find by the dates of his letters that he was corresponding at length and elaborately with the learned men of his time on technical points of scholarship, Biblical criticism...” (Froude, The Life and Letters, pp. 377, 394).

Critics are also quick to point out that Erasmus back-translated the last six verses of Revelation for his 1516 edition. But despite this charge, we see that Erasmus included a reading in Revelation 22:20 that exists in the Greek and not in any edition of the Vulgate (i.e. "αμην ναι ερχου (Amen. Even so, come)” instead of “amen veni (Amen. Come)"). This is one evidence that Erasmus was not confined to the readings contained in the few manuscripts placed before him during his editing of the 1516 edition. At the very least, Erasmus consulted notes such as the annotations of Laurentius Valla. As for the alleged "countless hundreds of printing errors" in Erasmus' first edition, these were corrected in later editions of the Textus Receptus by Erasmus himself, and never made their way into other Bibles.

God Used Only a Few Manuscripts to Preserve His Words

There is a theological problem with deriding the Textus Receptus on the basis that its original edition descends from just a few manuscripts. Our theory of textual criticism must be based on what the Bible says about textual transmission, not on the philosophies of liberal theologians. The Bible is clear that God can use only a handful of manuscripts to preserve his words.

The Bible describes a time when Hilkiah the high priest found the "book of the law" (2 Kings 22:8) or the "book of the covenant" (2 Kings 23:2) in the house of the LORD during the reign of Josiah. The book of the law, whether it was just the five books of Moses or a collection of all the biblical books written up until that time, had to be rediscovered during Josiah's reign because the previous wicked generations under Manasseh and Amon had apparently eradicated the book of the law from the land. This eradication of the biblical books was so widespread that even the high priest did not possess them until he discovered them in the temple.

This book found by Hilkiah became the ancestral copy of all the Hebrew manuscripts that exist today. One could speculate that Hilkiah found other manuscripts in other places over time, but that would be a speculation since the Bible does not say so. The Bible clearly portrays this single copy found in the temple as the sole catalyst for the great spiritual revival during Josiah's time and the rediscovery of God's words for subsequent generations. Ezra, a direct descendant of Hilkiah (Ezra 7:1), canonized the Old Testament and transmitted it to future generations. Ezra's Old Testament was surely based on Hilkiah's copy found in the temple. The readings of this copy eventually diverged into the various Old Testament streams extant today, such as the Masoretic, Dead Sea Scrolls, Samaritan and LXX. Whether or not Hilkiah or Ezra found other manuscripts besides the one found in the temple during Josiah's reign, the Bible is clear that the number of manuscripts does not matter as long as God providentially provides the manuscripts for a time of spiritual revival. King Josiah saw the hand of God in preserving this single copy and never doubted its authenticity or integrity. He caused the words of this single copy to be read to the people (2 Kings 23:2).

There is a strong parallel between Hilkiah and Desiderius Erasmus, the originator of the Textus Receptus. Both were men of high repute and rank. Both were upright while their contemporaries were apostate. Both caused God's words to be published after a time of spiritual darkness. Both were catalysts of a great spiritual awakening. The Textus Receptus was to the Reformation what Hilkiah's discovery was to the revival in Josiah's days. Modern textual critics need to learn what the Bible says about textual transmission. If God wants his words to be published for a time of spiritual awakening, he can do so through even just one manuscript.

Printings of the Textus Receptus

Erasmus was the author of five published editions from 1516 to 1535, the 1516 edition being the very first Textus Receptus.

There were approximately thirty distinct editions of the Textus Receptus made over the years. Each differs very slightly from the others. There have been over 500 printings. These variations include spelling, accents and breathing marks, word order and other minor differences. The editions of Stephens, Beza and the Elzevirs all present substantially the same text, and the variations are not of great significance and rarely affect the context.

The third edition of the Stephanus TR (1550) became the standard form of the Greek NT text in England. Theodore Beza published four independent editions from 1565 to 1604. His text was essentially a reprinting of the Stephanus third edition (1550) with minor changes. The Stephanus 1550 text as given in Beza’s edition of 1598 was the main source for the translators of the 1611 King James Version of the Bible.

The Elzevir brothers printed seven editions of the Greek NT between 1624 and 1678. Unlike the editions of Erasmus, Stephanus, and Beza before them, the Elzevirs’ were not the editors of the editions attributed to them, only the printers. The Elzevir brothers (1633) made another reprint of the Stephanus 1550 text which became the most popular text on the European continent.

There are approximately 93 differences between the Stephanus 1550 and the Beza 1598. These differences are minor, and pale into insignificance when compared with the approximately 6,000 differences (many of which are quite substantial) between the Alexandrian Critical Text and the Textus Receptus.