Textus Receptus Bibles

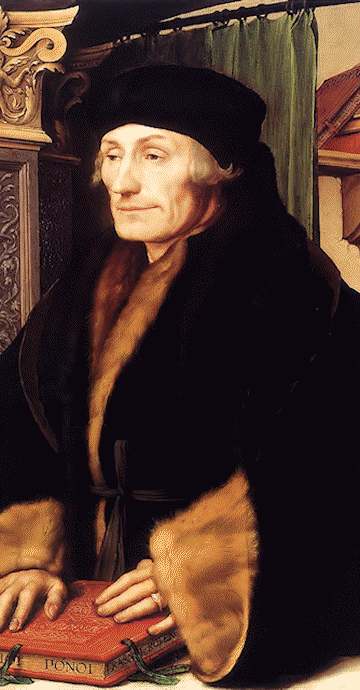

Who was Desiderius Erasmus?

- Part I Who was Desiderius Erasmus?

- Part II. How Many Manuscripts Have Been Destroyed?

- Part III. Is Textual Criticism Relevant Today?

Desiderius Erasmus

- Erasmus was born at Rotterdam in the Netherlands on October 27, 1466/9.

- After his parents died, when he was just 9 years old, Erasmus was sent to a monastic school run by the clergy of the Lebuïnuskerk (St. Lebuin's Church). From this point Erasmus was raised in a world of manuscripts. He became proficient in Latin and at this school, for the first time Greek was taught at a lower level than university.

- In 1492 Erasmus took his vows as a canon regular at Stein, in South Holland, and was ordained to the priesthood at the age of 25.

- Soon after his priestly ordination, he left the canonry when offered the post of secretary to the Bishop of Cambrai, Henry of Bergen. Erasmus was offered the position on account of his great skill in Latin and his reputation as a man of letters. To allow him to accept that post, he was given a temporary dispensation from his religious vows, although he still remained a priest. The dispensation was later made permanent, a considerable privilege at the time.

- In 1495, with Bishop Henry's consent and a small income, he went on to study at the University of Paris, in the Collège de Montaigu. The University was then the chief seat of scholastic learning in Europe..

- The centers of Erasmus's activity were Paris, Leuven (in the Duchy of Brabant [now in Belgium]), England, and Basel in Switzerland; yet he never firmly belonged in any one of these places.

- In 1499 he was invited by William Blount, 4th Baron Mountjoy to accompany him on his return to England.

- The time Erasmus spent in England was fruitful in making lifelong friendships, in the days of King Henry VIII with leaders of English thought: John Colet (Dean of St Pauls Cathedral), Thomas More (Lord High Chancellor of England ), John Fisher (English Bishop and theologian), Thomas Linacre (humanist scholar and physician) and William Grocyn (lecturer in Greek at Oxford).

- He also gained valuable letters of introduction to the royal courts of Europe which allowed him access to institutions throughout Europe with biblical manuscripts.

-

Erasmus had mastered the Greek language to the extent that he understood its true worth in theological studies.

In a letter to Antoon van Bergen in 1501 Erasmus wrote:

"Latin scholarship, however elaborate, is maimed and reduced by half without Greek. For whereas we Latins have but a few small streams, a few muddy pools, the Greeks possess crystal-clear springs and rivers that run with gold. I can see what utter madness it is even to put a finger on that part of theology which is specially concerned with the mysteries of the faith unless one is furnished with the equipment of Greek as well, since the translators of Scripture, in their scrupulous manner of construing the text, offer such literal versions of Greek idioms that no one ignorant of that language could grasp even the primary, or, as our own theologians call it, literal, meaning." [1]

- In 1506 he was finally able, with the aid of his English friends, to attain his greatest desire; a journey to Italy. On his way there he received at Turin the degree of Doctor of Divinity; at Bologna, Padua, and Venice, the academic centers of Upper Italy, he was greeted with enthusiastic honor by the most distinguished humanists, and he spent some time in each of these cities.

- In Venice, Erasmus formed an intimate friendship with the famous printer Aldus Manutius. His reception at Rome was equally flattering; the cardinals, especially Giovanni de' Medici (later Pope Leo X), and Domenico Grimani, were particularly gracious to him.

- Such was the fame of Erasmus by this time he was able to corresponded with scholars throughout Europe and gain access to readings of the most important biblical manuscripts of his day. Extant copies of his correspondence exist today including his correspondence with the Vatican library.

- Erasmus returned to England and at the University of Cambridge, he was the Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity and had the option of spending the rest of his life as an English professor. He stayed at Queens' College, Cambridge from 1510 to 1515. It is most likely that the majority of his work on New Testament Greek variants was collated in this period.

Fredrick Nolan

Frederick Nolan, writing in 1815, states, in addition to the manuscripts which Erasmus owned or had seen himself, he gathered readings from various European nations through his broad friendships in universities, libraries, and monasteries. He noted; “I have a room full of letters from men of learning...” “We find by the dates of his letters that he was corresponding at length and elaborately with the learned men of his time on technical points of scholarship, Biblical criticism...”. [2]

- Erasmus had been working for years on two projects: his collation of Greek texts and a fresh Latin New Testament. In 1512, he began his work on this Latin New Testament. He collected all the Vulgate manuscripts he could find to create a critical edition. Then he polished the Latin and declared, "It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin."

- While his intentions for publishing a fresh Latin translation are clear, it is less clear why he included the Greek text. Though some speculate that he intended to produce a critical Greek text or that he wanted to beat the Complutensian Polyglot into print, there is no evidence to support this. Erasmus wrote: "There remains the New Testament translated by me, with the Greek facing, and notes on it by me." [3] He further demonstrated the reason for the inclusion of the Greek text when defending his work: "But one thing the facts cry out, and it can be clear, as they say, even to a blind man, that often through the translator’s clumsiness or inattention the Greek has been wrongly rendered; often the true and genuine reading has been corrupted by ignorant scribes, which we see happen every day, or altered by scribes who are half-taught and half-asleep." [4]

- It is not hard to see from his statements that Erasmus included the Greek text to permit qualified readers to verify the quality of his Latin version. But by first calling the final product Novum Instrumentum omne ("All of the New Teaching") and later Novum Testamentum omne ("All of the New Testament") he also indicated (at that time), he considered a text in which the Greek and the Latin versions were consistently comparable to be the essential core of the church's New Testament tradition.

- In 1521 Erasmus moved to Basel, Switzerland.

- The third edition of Novum Testamentum omne (1522) was used by William Tyndale for the first English New Testament translated from the Greek (Worms, 1526), and was the basis for the 1550 Robert Stephanus edition used by the translators of the Geneva Bible and King James Version of the English Bible.

- Erasmus published a fourth edition in 1527 containing parallel columns of Greek, Latin Vulgate and Latin texts.

- In 1535 Erasmus published the fifth (and final) edition which dropped the Latin Vulgate column but was otherwise similar to the fourth edition. Later versions of the Greek New Testament by others, based on Erasmus's Greek New Testament, became known collectively as the Textus Receptus.

- Erasmus dedicated his work as a patron of learning and regarded this work as his chief service to the cause of Christianity.

- Immediately after completing his New Testament, he began the publication of his Paraphrases of the New Testament, a popular presentation of the contents of the several books. These, like all of his writings, were published in Latin but were quickly translated into other languages, with his encouragement.

- Erasmus died suddenly in Basel in 1536 while preparing to return to Brabant, and was buried in the Basel Minster, the former cathedral of the city. A bronze statue of him was erected in his city of birth in 1622, replacing an earlier work in stone.

- Martin Luther's movement began in the year following the publication of the Erasmus New Testament. The issues between the growing religious movements, which would later become known as Protestantism, and the Catholic Church had become very clear. However, the irony of it all, is that while Erasmus was trying to reform the text of the Catholic Church it was the Protestants that went on to adopt the Textus Receptus.

Published Works:

- Adagia (1500)

- Enchiridion militis Christiani (1503)

- The Praise of Folly (1511)

- Copia: Foundations of the Abundant Style (1512)

- Disticha de moribus nomine Catonis (1513)

- Sileni Alcibiadis (1515)

- Novum Instrumentum omne (1516)

- The Education of a Christian Prince (1516)

- Bellum (essay, 1517)

- Colloquia (1518); 12 more eds. by 1533

- Ciceronianus (1528)

- De recta Latini Graecique Sermonis Pronunciatione (1528)

- De pueris statim ac liberaliter instituendis (1529)

- A handbook on manners for children (1530)

- Consultatio de Bello Turcis Inferendo (1530)

- A Playne and Godly Exposition or Declaration of the Commune Crede (1533)

- Ecclesiastes (1535)

- De octo orationis partium constructione libellus (1536).

- Apophthegmatum opus (1539)

- The first volume of the Paraphrase of Erasmus vpon the newe testamente (1548)

Footnotes:

-

Epistle 149 to Antoon van Bergen 1501, in The Correspondence of Erasmus:

Epistle 142 to 297 (1501 to 1514), R. A. B. Mynors and D. F. S. Thomson, trans. (Toronto, CA: University of Toronto, 1975), p. 25. - Froude, The Life and Letters, pp. 377, 394

- Epistle 305 in Collected Works of Erasmus. Vol. 3: Letters 298 to 445, 1514–1516 (tr. R.A.B. Mynors and D.F.S. Thomson; annotated by James K. McConica; Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976)

- Epistle 337 in Collected Works of Erasmus Vol. 3, p. 134.