Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 3:1 | This is a true sayege: Yf a ma covet ye office of a Bisshoppe, he desyreth a good worke. |

| 3:2 | But a Bisshoppe must be blamelesse, the hussbade of one wife, sober, discrete, manerly, harberous, apte to teach: |

| 3:3 | Not geuen to moch wyne, no fighter, not geuen to filthy lucre: but gentle, abhorrynge stryfe, abhorrynge couetousnes: |

| 3:4 | & one that ruleth his awne house honestly, hauynge obedient children with all honestye. |

| 3:5 | (But yf a man can not rule his owne house, how shal he care for the congregacion of God?) |

| 3:6 | He maye not be a yoge scolar, lest he be puft vp, and fall in to the iudgment of ye euell speaker. |

| 3:7 | He must also haue a good reporte of them which are without, lest he fall in to the rebuke and snare of the euell speaker. |

| 3:8 | Likewyse must the mynisters be honest, not double tonged, not geuen to moch wyne, nether vnto fylthie lucre, |

| 3:9 | but hauynge the mystery of faith in pure conscience. |

| 3:10 | And let them first be proued, and then let them mynister, yf they be blamelesse. |

| 3:11 | Euen so must their wyues be honest, not euell speakers, but sober and faithfull in all thinges. |

| 3:12 | Let the mynisters be, euery one the hussbade of one wyfe, and soch as rule their children well, and their owne housholdes. |

| 3:13 | For they that mynister well, get them selues a good degree and greate libertye in the faith which is in Christ Iesu. |

| 3:14 | These thinges wryte I vnto the, trustinge shortly to come vnto the: |

| 3:15 | but yf I tary loge, that then thou mayest yet haue knowlege, how thou oughtest to behaue thy selfe in Gods house, which is the congregacion of the lyuynge God, the piler and grounde of trueth: |

| 3:16 | and without naye, greate is that mystery of godlynes. God was shewed in the flesh: was iustified in the sprete: was sene of angels: was preached vnto the Heythen: was beleued on in the worlde: was receaued vp in glory. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

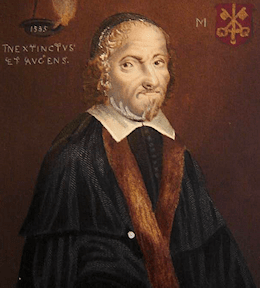

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.