Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 10:1 | Deed flyes yt corruppe swete oyntment & make it to styncke, are somthinge more worth then the wy?dome & honor of a foole. |

| 10:2 | A wyse mans hert is vpon the right hande, but a fooles hert is vpon the left. |

| 10:3 | A dotinge foole thinketh, yt euery ma doth as foolishly as himself. |

| 10:4 | Yf a principall sprete be geue the to beare rule, be not negliget the in thine office: for so shal greate wickednesse be put downe, as it were wt a medecyne. |

| 10:5 | Another plage is there, which I haue sene vnder the Sonne: namely, ye ignoraunce yt is comonly amonge prynces: |

| 10:6 | in yt a foole sytteth in greate dignite, & the rich are sett downe beneth: |

| 10:7 | I se seruauntes ryde vpon horses, & prynces goinge vpon their fete as it were seruauntes. |

| 10:8 | But he yt dyggeth vp a pytt, shall fall therin himself: & who so breaketh downe the hedge, a serpent shal byte him. |

| 10:9 | Who so remoueth stones, shall haue trauayle withall: and he that heweth wod, shalbe hurt therwith. |

| 10:10 | When an yron is blont, and ye poynt not sharpened, it must be whett againe, and that with might: Euen so doth wi?dome folowe diligence. |

| 10:11 | A babler of his tonge is no better, then a serpent that styngeth without hyssynge. |

| 10:12 | The wordes out of a wyse mans mouth are gracious, but the lippes of a foole wil destroye himself. |

| 10:13 | The begynnynge of his talkynge is foolishnes, and the last worde of his mouth is greate madnesse. |

| 10:14 | A foole is so full of wordes, that a man can not tell what ende he wyll make: who wyl then warne him to make a conclucion? |

| 10:15 | The laboure of ye foolish is greuous vnto the, while they knowe not how to go in to the cite. |

| 10:16 | Wo be vnto the (O thou realme and londe) whose kynge is but a childe, and whose prynces are early at their banckettes. |

| 10:17 | But well is the (O thou realme and londe) whose kinge is come of nobles, and whose prynces eate in due season, for strength and not for lust. |

| 10:18 | Thorow slouthfulnesse the balkes fall downe, and thorow ydle hades it rayneth in at the house. |

| 10:19 | Meate maketh men to laugh, and wyne maketh them mery: but vnto money are all thinges obedient. |

| 10:20 | Wysh the kynge no euell in yi thought, and speake no hurte of ye ryche in thy preuy chambre: for a byrde of the ayre shal betraye thy voyce, and wt hir fethers shal she bewraye thy wordes. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

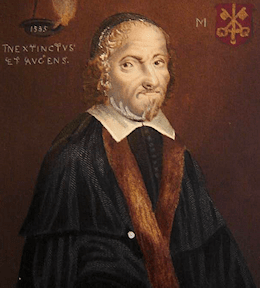

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.