Textus Receptus Bibles

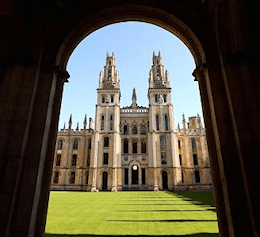

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 3:1 | By night on my bed I sought him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, but I found him not. |

| 3:2 | I will rise now, and go about the city in the streets, and in the broad ways I will seek him whom my soul loveth: I sought him, but I found him not. |

| 3:3 | The watchmen that go about the city found me: to whom I said, Saw ye him whom my soul loveth? |

| 3:4 | It was but a little that I passed from them, but I found him whom my soul loveth: I held him, and would not let him go, until I had brought him into my mother's house, and into the chamber of her that conceived me. |

| 3:5 | I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, till he please. |

| 3:6 | Who is this that cometh out of the wilderness like pillars of smoke, perfumed with myrrh and frankincense, with all powders of the merchant? |

| 3:7 | Behold his bed, which is Solomon's; threescore valiant men are about it, of the valiant of Israel. |

| 3:8 | They all hold swords, being expert in war: every man hath his sword upon his thigh because of fear in the night. |

| 3:9 | King Solomon made himself a chariot of the wood of Lebanon. |

| 3:10 | He made the pillars thereof of silver, the bottom thereof of gold, the covering of it of purple, the midst thereof being paved with love, for the daughters of Jerusalem. |

| 3:11 | Go forth, O ye daughters of Zion, and behold king Solomon with the crown wherewith his mother crowned him in the day of his espousals, and in the day of the gladness of his heart. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.