Textus Receptus Bibles

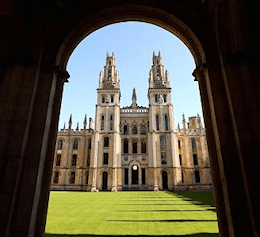

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 6:1 | Whither is thy beloved gone, O thou fairest among women? whither is thy beloved turned aside? that we may seek him with thee. |

| 6:2 | My beloved is gone down into his garden, to the beds of spices, to feed in the gardens, and to gather lilies. |

| 6:3 | I am my beloved's, and my beloved is mine: he feedeth among the lilies. |

| 6:4 | Thou art beautiful, O my love, as Tirzah, comely as Jerusalem, terrible as an army with banners. |

| 6:5 | Turn away thine eyes from me, for they have overcome me: thy hair is as a flock of goats that appear from Gilead. |

| 6:6 | Thy teeth are as a flock of sheep which go up from the washing, whereof every one beareth twins, and there is not one barren among them. |

| 6:7 | As a piece of a pomegranate are thy temples within thy locks. |

| 6:8 | There are threescore queens, and fourscore concubines, and virgins without number. |

| 6:9 | My dove, my undefiled is but one; she is the only one of her mother, she is the choice one of her that bare her. The daughters saw her, and blessed her; yea, the queens and the concubines, and they praised her. |

| 6:10 | Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners? |

| 6:11 | I went down into the garden of nuts to see the fruits of the valley, and to see whether the vine flourished, and the pomegranates budded. |

| 6:12 | Or ever I was aware, my soul made me like the chariots of Amminadib. |

| 6:13 | Return, return, O Shulamite; return, return, that we may look upon thee. What will ye see in the Shulamite? As it were the company of two armies. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.