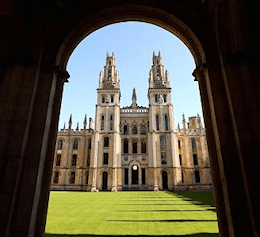

Textus Receptus Bibles

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 7:1 | How beautiful are thy feet with shoes, O prince's daughter! the joints of thy thighs are like jewels, the work of the hands of a cunning workman. |

| 7:2 | Thy navel is like a round goblet, which wanteth not liquor: thy belly is like an heap of wheat set about with lilies. |

| 7:3 | Thy two breasts are like two young roes that are twins. |

| 7:4 | Thy neck is as a tower of ivory; thine eyes like the fishpools in Heshbon, by the gate of Bathrabbim: thy nose is as the tower of Lebanon which looketh toward Damascus. |

| 7:5 | Thine head upon thee is like Carmel, and the hair of thine head like purple; the king is held in the galleries. |

| 7:6 | How fair and how pleasant art thou, O love, for delights! |

| 7:7 | This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes. |

| 7:8 | I said, I will go up to the palm tree, I will take hold of the boughs thereof: now also thy breasts shall be as clusters of the vine, and the smell of thy nose like apples; |

| 7:9 | And the roof of thy mouth like the best wine for my beloved, that goeth down sweetly, causing the lips of those that are asleep to speak. |

| 7:10 | I am my beloved's, and his desire is toward me. |

| 7:11 | Come, my beloved, let us go forth into the field; let us lodge in the villages. |

| 7:12 | Let us get up early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine flourish, whether the tender grape appear, and the pomegranates bud forth: there will I give thee my loves. |

| 7:13 | The mandrakes give a smell, and at our gates are all manner of pleasant fruits, new and old, which I have laid up for thee, O my beloved. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.