Textus Receptus Bibles

Coverdale Bible 1535

| 1:1 | Salomons Balettes, called Cantica Canticorum. |

| 1:2 | O that thy mouth wolde geue me a kysse, for yi brestes are more pleasaunt then wyne, |

| 1:3 | & that because of the good and pleasaunt sauoure. Thy name is a swete smellynge oyntment, therfore do the maydens loue the: |

| 1:4 | yee that same moueth me also to renne after the. The kynge hath brought me into his preuy chambre. We wil be glad & reioyce in the, we thynke more of thy brestes then of wyne: well is them that loue the. |

| 1:5 | I am black (o ye doughters of Ierusale) like as the tentes of the Cedarenes, and as the hanginges of Salomon: |

| 1:6 | but yet am I faire & welfauoured withal. Maruell not at me yt I am so black, & why? ye Sonne hath shyned vpo me. For whan my mothers childre had euell wil at me, they made me ye keper of the vynyarde. Thus was I fayne to kepe a vynyarde, which was not myne owne. |

| 1:7 | Tell me (o thou whom my soule loueth) where thou fedest, where thou restest at the noone daye: lest I go wronge, and come vnto the flockes of thy companyons, |

| 1:8 | Yf thou knowe not yi self (o thou fayrest amoge women) tha go yi waye forth after ye fotesteppes of the shepe, as though thou woldest fede yi goates besyde ye shepherdes tentes. |

| 1:9 | There wil I tary for the (my loue) wt myne hoost & with my charettes, which shalbe no fewer then Pharaos. |

| 1:10 | Then shal thy chekes & thy neck be made fayre, & hanged wt spages & goodly iewels: |

| 1:11 | a neck bande of golde wil we make ye wt syluer bottons. |

| 1:12 | When the kynge sytteth at the table, he shal smell my Nardus: |

| 1:13 | for a bodell of Myrre (o my beloued) lyeth betwixte my brestes. |

| 1:14 | A cluster of grapes of Cypers, or of the vynyardes of Engaddi, art thou vnto me, O my beloued. |

| 1:15 | O how fayre art thou (my loue) how fayre art thou? thou hast doues eyes. |

| 1:16 | O how fayre art thou (my beloued) how well fauored art thou? Oure bed is decte with floures, |

| 1:17 | ye sylinges of oure house are of Cedre tre, & oure balkes of Cypresse. |

Coverdale Bible 1535

The Coverdale Bible, compiled by Myles Coverdale and published in 1535, was the first complete English translation of the Bible to contain both the Old and New Testament and translated from the original Hebrew and Greek. The later editions (folio and quarto) published in 1539 were the first complete Bibles printed in England. The 1539 folio edition carried the royal license and was, therefore, the first officially approved Bible translation in English.

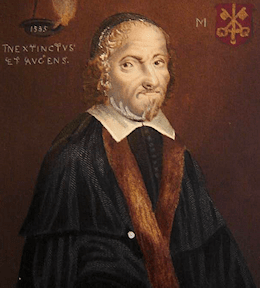

Tyndale never had the satisfaction of completing his English Bible; but during his imprisonment, he may have learned that a complete translation, based largely upon his own, had actually been produced. The credit for this achievement, the first complete printed English Bible, is due to Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), afterward bishop of Exeter (1551-1553).

The details of its production are obscure. Coverdale met Tyndale in Hamburg, Germany in 1529, and is said to have assisted him in the translation of the Pentateuch. His own work was done under the patronage of Oliver Cromwell, who was anxious for the publication of an English Bible; and it was no doubt forwarded by the action of Convocation, which, under Archbishop Cranmer's leading, had petitioned in 1534 for the undertaking of such a work.

Coverdale's Bible was probably printed by Froschover in Zurich, Switzerland and was published at the end of 1535, with a dedication to Henry VIII. By this time, the conditions were more favorable to a Protestant Bible than they had been in 1525. Henry had finally broken with the Pope and had committed himself to the principle of an English Bible. Coverdale's work was accordingly tolerated by authority, and when the second edition of it appeared in 1537 (printed by an English printer, Nycolson of Southwark), it bore on its title-page the words, "Set forth with the King's most gracious license." In licensing Coverdale's translation, King Henry probably did not know how far he was sanctioning the work of Tyndale, which he had previously condemned.

In the New Testament, in particular, Tyndale's version is the basis of Coverdale's, and to a somewhat less extent this is also the case in the Pentateuch and Jonah; but Coverdale revised the work of his predecessor with the help of the Zurich German Bible of Zwingli and others (1524-1529), a Latin version by Pagninus, the Vulgate, and Luther. In his preface, he explicitly disclaims originality as a translator, and there is no sign that he made any noticeable use of the Greek and Hebrew; but he used the available Latin, German, and English versions with judgment. In the parts of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not published he appears to have translated mainly from the Zurich Bible. [Coverdale's Bible of 1535 was reprinted by Bagster, 1838.]

In one respect Coverdale's Bible was groundbreaking, namely, in the arrangement of the books of the. It is to Tyndale's example, no doubt, that the action of Coverdale is due. His Bible is divided into six parts -- (1) Pentateuch; (2) Joshua -- Esther; (3) Job -- "Solomon's Balettes" (i.e. Canticles); (4) Prophets; (5) "Apocrypha, the books and treatises which among the fathers of old are not reckoned to be of like authority with the other books of the Bible, neither are they found in the canon of the Hebrew"; (6) the New Testament. This represents the view generally taken by the Reformers, both in Germany and in England, and so far as concerns the English Bible, Coverdale's example was decisive.