Textus Receptus Bibles

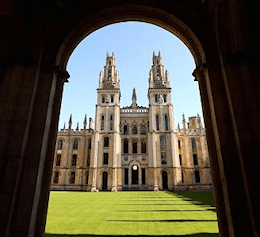

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

| 13:1 | Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. |

| 13:2 | And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing. |

| 13:3 | And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. |

| 13:4 | Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, |

| 13:5 | Doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; |

| 13:6 | Rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; |

| 13:7 | Beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. |

| 13:8 | Charity never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away. |

| 13:9 | For we know in part, and we prophesy in part. |

| 13:10 | But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away. |

| 13:11 | When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. |

| 13:12 | For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. |

| 13:13 | And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity. |

King James Bible (Oxford) 1769

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of twenty-years work by Francis Sawyer Parris, who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762 and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763. This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney.